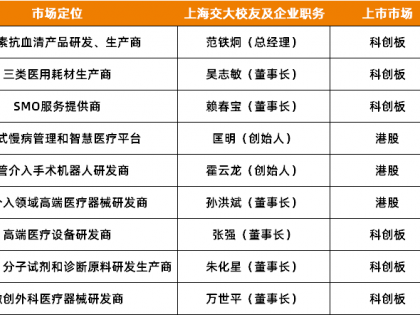

Buffalo researchers have managed to grow new forms of erythromycin, seen here in petri dishes (circled in red) (Credit: Guojian Zhang)

Scientists use colonies of E. coli as antibiotic production factories

By Chris Wood

June 3, 2015

A team of researchers from the University at Buffalo School of Engineering has turned to colonies of E. coli bacteria to produce new forms of antibiotics. The study made use of a harmless form of E. coli, and several of the resulting drugs may be equipped to tackle harmful, drug-resistant bacteria.

It's long been suspected that E. coli could be a source of new forms of antibiotics. The bacteria grows very fast, allowing researchers to quickly prototype treatments, and the species is very accepting of new genes, making it a good option for drug engineering.

The University at Buffalo researchers spent 11 years working with E. coli, manipulating the bacteria to produce the material necessary for creating erythromycin, which is used in the treatment of various illnesses from whooping cough to pneumonia.

The team describes the process as being akin to stocking a factory with the components necessary to build a car, with each of the produced materials manipulating or combining with three key chemical compounds as if on a production line, eventually forming erythromycin.

once the bacteria is prepped and ready for production to begin, it's possible to tweak the process so that slightly different versions of erythromycin are produced, differing from those currently used in medical treatment. To build these differently-shaped erythromycin, the team used enzymes to attach 16 different sugar molecules to a molecule in the production process, itself known as 6-deoxyerythronolide B.

Each of the sugar molecules successfully adhered to the production molecules, giving rise to more than 40 new versions of erythromycin at the end of the assembly line. After laboratory testing, the researchers found that three of the samples were able to fight eyrthromycin-resistant bacteria. Overall, it's a very promising start for a new avenue of drug development.

"The system we’ve created is surprisingly flexible, and that’s one of the great things about it," said the university's Professor Blaine Pfeifer. "We have established a platform for using E. coli to produce erythromycin, and now that we’ve got it, we can start altering it in new ways."

The researchers published the findings of their study in the journal Science Advances.

Source: University at Buffalo

2015年6月1日

纽约州布法罗(Scicasts) -像奶农趋于一群奶牛生产牛奶,研究人员正在趋向于细菌大肠杆菌(大肠杆菌)的菌落,产生抗生素的新形式-包括三名,显示诺言战斗抗药性细菌。

这项研究在科学进展杂志上发表5月29日,率领由布莱恩A.普法伊费尔,化学和生物工程在大学副教授工程与应用科学学院布法罗。 他的团队包括第一作者张国建,易立和雷芳,都在化学和生物工程系。

对于十几年来,普法伊费尔一直在研究如何工程师大肠杆菌产生新的品种红霉素,一个流行的抗生素。 在新的研究中,他和他的同事报告说,他们已经成功地做到了这一点,利用大肠杆菌合成数十药物的新形式有从现有的版本略有不同的结构。

这三个新品种红霉素种枯草芽孢杆菌,可以抵抗红霉素的临床使用的原始形式的成功杀死细菌。

“我们正在集中在试图想出新的抗生素,可以克服抗生素耐药性,我们认为这是向前迈进的重要一步,”普法伊费尔博士说。

“我们不仅创造红霉素新的类似物,而且还开发了一个平台,利用大肠杆菌生产药物,”他说。 “这将打开大门在将来额外的工程的可能性; 这可能会导致药物的更加新的形式。“

该研究是用在上升抗生素抗性尤其重要。 红霉素是用于治疗各种疾病,肺炎和百日咳到皮肤和泌尿道感染。

大肠杆菌作为工厂

获得大肠杆菌产生新的抗生素已经东西圣杯的研究人员在外地。

这是因为大肠杆菌的快速增长,从而加快实验步骤和艾滋病努力发展和扩大生产的药品。 该品种也接受新的基因相对容易,使其成为工程总理候选人。

虽然新闻报道往往侧重于大肠杆菌的危险,大多数类型的这种细菌是无害的实际,包括那些在实验室中使用的普法伊费尔的球队。

在过去的11年中,普法伊费尔的研究主要集中于操纵大肠杆菌,使机体产生的一切必要创造红霉素的材料。 你可以认为这就像放养了所有必要的部分工厂和设备制造一辆汽车或飞机。

随着研究的完成这一阶段,普法伊费尔已经转向下一个目标:调整他的工程大肠杆菌生产红霉素,让他们使药物比医院现在使用的版本略有不同的方式。

这是新的科学进展纸的话题。

创建红霉素的过程开始三个称为代谢前体基本构造块 - 一种化合物相结合,并操纵通过流水线状工艺以形成最终产品,红霉素。

要建立新品种略有不同形状红霉素,科学家们从理论上可以针对任何部分流水线,使用各种技术来固定零件,从原稿略有不同的结构。 (在汽车装配线,这将类似于拧上的门把手具有稍微不同的形状。)

在新的研究中,普法伊费尔的团队专注于在以前很少受到关注,从研究人员,接近尾声的一个步骤建设过程中的一步。

研究人员集中研究用酶来连接16个不同的糖分子形状到一个名为6 deoxyerythronolide B.这些糖分子的每一位成功坚持分子,领导,在流水线的末端,以超过40个新类似物红霉素 - 其中三个表现出打红霉素耐药细菌在实验室的实验能力。

“我们已经创建的系统是出奇的灵活,这就是关于它的伟大的事情之一,”普法伊费尔说。 “我们已经建立了一个平台,利用大肠杆菌生产红霉素,现在我们已经得到了它,我们就可以开始改变它以新的方式。”

文章改编自纽约水牛城一个州立大学新闻发布。

出版: 裁剪途径模块化红霉素类似物异源工程在大肠杆菌中 章国建,易立,丽凤,布莱恩A.普法伊费尔的生物合成。 科学进展

延伸阅读:

For decades, scientists have looked for ways to make alternate versions of antibiotics naturally produced by bacteria and fungi in hopes of expanding the activities of available drugs. In a study published today (May 29) in Science Advances, researchers from the State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo report a technique that allowed them to make 42 new versions of the antibiotic erythromycin, three of which showed activity against drug-resistant bacteria.

“I was going into it thinking maybe we’d make a fifth of the number [of compounds] we actually made,” said Blaine Pfeifer, a chemical and biological engineer at Buffalo, who led the study.

The bacteria Saccharopolyspora erythraea naturally produces erythromycin, but like many antibiotic-producing organisms, S. erythraea doesn’t make the best laboratory strain. Unique growth requirements and a lack of genetic tools make it difficult to engineer these organisms to make analogs of their natural products. So the scientists introduced altered genes that encode the enzymes along the antibiotic’s biochemical pathway through a process called combinatorial biosynthesis. “Isolation of new molecules from nature is very often time consuming and labor intensive,” said Jixun Zhan, who studies metabolic engineering at Utah State University and was not involved in the work. “Using combinatorial biosynthesis is a more efficient way to make new molecules.”

To get to point wher they could alter the biosynthesis of erythromycin, Pfeifer and his colleagues worked to “transplant” its entire biochemical pathway into the lab-friendly species E. coli. Getting E. coli to express and use the enzymes correctly “took years of tinkering and optimization,” said Pfeifer.

In 2010, Pfeifer’s lab accomplished this feat, laying the groundwork for the current study. “once we went through all of the growing pains of establishing the process, we had this unprecedented toolbox,” he said.

For the present study, Guojian Zhang—a postdoc in Pfeifer’s lab—used this toolbox to build upon the system by introducing enzymatic pathways that could alter a sugar group added toward the end of erythromycin synthesis. To reconstitute these pathways in E. coli, Zhang borrowed genes from several other bacterial species. “He was kind of doing a Frankenstein thing, pulling all of these enzymes together,” said Pfeifer.

Zhang designed 16 different pathways and introduced each one into a different E. coli strains. He then fed the bacteria an erythromycin precursor—which was also produced in E. coli—and analyzed the resulting products using mass spectrometry. All of the pathways produced unique sugar groups that were successfully attached to the erythromycin precursor, forming 42 analog compounds. He tested them against an erythromycin-resistant strain of Bacillus subtilis and found that three of these compounds inhibited the bacterium’s growth.

Pfeifer said he was surprised at how well the technique worked. “This system had a level of flexibility that we didn’t anticipate,” he told The Scientist. The flexibility of the enzymes to accept alternate sugar substrates was a critical feature of the study, said Kira Weissman, a biological engineer at the University of Lorraine in France who was not involved in the work.

Going forward, Pfeiffer said his team plans to target other sugar groups on the erythromycin molecule. “There are a lot of opportunities for variation with this system because it is so complex,” he said.

Zhang said the experimental design could enable other researchers to make similar variations of other natural products, or “unnatural natural products,” as they’re commonly called. The erythromycin pathway is the best-characterized natural product pathway, making it a sort of model system for biosynthetic engineering. “They started out with a system that was nicely producing,” said Weissman.

Much work remains to generalize this technique to other compounds. Pfeiffer’s team is approaching this challenge by first working to transplant pathways for other antibiotics and for cancer drugs into E. coli. “Theoretically, this idea could be applied to all sorts of natural products,” he said.

G. Zhang, et al. “Tailoring pathway modularity in the biosynthesis of erythromycin analogs heterologously engineered in E. coli,” Science Advances, doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500077, 2015.

几十年来,科学家们为使在扩大现有药物的活动希望细菌和真菌的自然产生的抗生素替代版本的方法。今天发表的一项研究(五月二十九日)科学的进步,研究人员从纽约州立大学布法罗(SUNY)报告的技术,允许他们使抗生素红霉素42新版本,其中三具有抗耐药菌活性。

“我要到它想也许我们会做五分之一的化合物的数量[ ]实际上,”布莱恩说普法,化学和生物工程师在布法罗,研究LED的人。

红色糖多孢菌的细菌自然产生的红霉素,但像许多抗生素产生菌,美国红不让最好的实验室菌株。独特的生长条件和缺乏的遗传工具难以工程师这些生物体使其天然产物类似物。所以科学家们介绍了改变基因编码在抗生素的生化途径的酶的过程称为组合生物合成。“从自然分离的新的分子往往是耗费时间和劳动力密集型的,说:”急寻湛,谁研究代谢工程在犹他州立大学并没有参与这项工作。“利用组合生物合成是一个更有效的方式,使新的分子。”

去的地方他们可以改变红霉素的生物合成,Pfeifer和他的同事们在“移植”的生化途径进入实验室友好种大肠杆菌。让大肠杆菌表达和使用正确的“把酶的修修补补,优化年,说:”普法。

2010,Pfeifer实验室完成了这一壮举,奠定研究基础。“当我们经历了所有的建立过程的成长的烦恼,我们有这前所未有的工具箱,”他说。

对于目前的研究,zhang-a国博士后Pfeifer实验室用这个工具箱建立在系统中引入酶途径能够改变糖组添加对红霉素合成的结束。重建这些途径在大肠杆菌中,张某借用其他一些种类的细菌基因。“他是一个怪人的事做,让所有的这些酶在一起,说:”普法。

设计了16种不同的途径,并介绍了张每个人到一个不同的大肠杆菌菌株。然后他喂细菌红霉素为前驱物,也产生在大肠杆菌和分析产生的产品采用质谱法。所有的途径产生独特的糖组成功地连接到红霉素的前体,形成42个模拟化合物。他测试了他们对枯草芽孢杆菌的红霉素耐药菌株,发现三种化合物抑制细菌的生长。

Pfeifer说他惊讶的技术工作以及如何。“这个系统有了一定程度的灵活性,我们没有预料到的,”他告诉科学家。酶的灵活性接受替代糖基是一个关键的功能的研究,他说基拉,生物工程师在法国洛林大学,谁没有参与这项工作。

展望未来,菲佛说,他的团队计划目标对红霉素分子其他糖组。“有很多机会与这个系统变化,因为它是如此的复杂,”他说。

张说,实验设计可以使其他研究者能够让其他天然产物类似的变化,或“非天然的产品,他们通常被称为“。红霉素通路是最好的天然产品的途径,使其成为一种用于生物合成工程模型系统。“他们开始了一个很好的生产系统,”他说。

仍有许多工作要推广这种技术的其他化合物。菲佛的团队正在接近这一挑战的第一个工作对其他抗生素的途径移植和癌症药物进入大肠杆菌。“从理论上讲,这种思想可以应用于各种自然的产品,”他说。

G. Zhang,et al.。“裁剪路径模块在红霉素类似物在大肠杆菌中的异源基因工程合成,“科学进展,DOI:10.1126/sciadv.1500077,2015。